Environmental Racism: Old Wine in a New Bottle

By Dr Deborah M. Robinson

|

Environmental Racism: Old Wine in a New Bottle

By Dr Deborah M. Robinson |

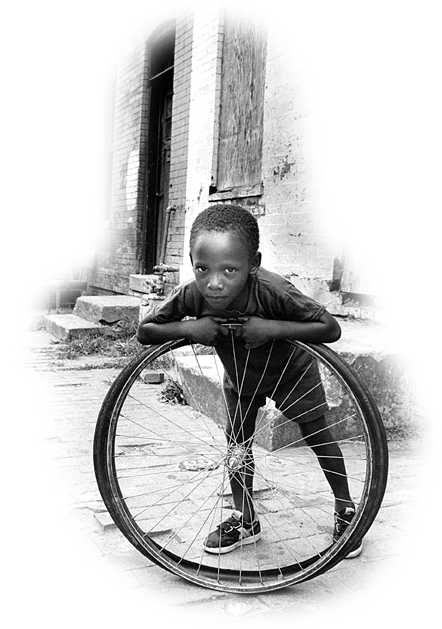

Photo: Rick Reinhard, WCC |

This short article reviews the history of the environmental justice movement in the United States, provides examples of environmental racism in the US as well as globally, and concludes with a discussion of the World Conference Against Racism and the opportunity it provides to place firmly this newer manifestation of racism on the international agenda.

Environmental racism can be defined as: Others have added to that definition by saying environmental racism refers to "any government, institutional, or industry action, or failure to act, that has a negative environmental impact which disproportionately harms - whether intentionally or unintentionally - individuals, groups, or communities based on race or colour."2 It is important though, to understand environmental racism in an historical context. "The exploitation of people of colour has taken the form of genocide, chattel slavery, indentured servitude and racial discrimination - in employment, housing and practically all aspects of life. Today we suffer from the remnants of this sordid history, as well as from new and institutionalised forms of racism, facilitated by the massive post-World War II expansion of the petrochemical industry."3 In the United States, the victims of environmental racism are African Americans, Latinos, Native Americans, Asians, and Pacific Islanders, who are more likely than Whites to live in environmentally hazardous conditions. Three out of five African Americans live in communities with uncontrolled toxic waste sites. Native American lands and sacred places are home to extensive mining operations and radioactive waste sites. Three of the five largest commercial hazardous waste landfills are located in predominantly African American and Latino communities. As a consequence, the residents of these communities suffer shorter life spans, higher infant and adult mortality, poor health, poverty, diminished economic opportunities, substandard housing, and an overall degraded quality of life. |

| For more than a decade environmental racism in the United States has been well-documented by NGOs, universities, and even the US government.6 However, the government has provided no effective remedies to the victims of these racist practices, nor has it taken effective action to stop such practices from occurring in the future. | Environmental racism, therefore, is a new mani-festation of historic racial oppression. It is merely "old wine in a new bottle." Many people trace the birth of the environmental justice movement in the United States to the 1991 First National People of Colour Environmental Leadership Summit held in Washington, DC, but there were many important antecedents to this event. In 1982, North Carolina State officials decided to locate a PCB (polychlorinated-biphenyl) landfill in a predominately African American community. In response, protestors lay down in the streets trying to block trucks carrying the toxic waste to the landfill and over 500 people were arrested. This act of civil disobedience was the first time anyone was jailed for trying to halt a toxic waste landfill.4 One of those arrested was US Congressman Walter Fauntroy. He later asked the US General Accounting Office (a federal agency) to determine the correlation between the location of hazardous waste landfills and the racial and economic status of the surrounding communities in that region. The GAO study concluded that, "Blacks make up the majority of the population in three out of four communities where landfills are located."5 The landmark 1987 report by the United Church of Christ Commission for Racial Justice, Toxic Wastes and Race, extended the GAO study. It was based on a national study that mapped the location of toxic waste sites and the racial composition of the community. They found that people of colour were twice as likely as White people to live in a community with a commercial hazardous waste management facility and three times as likely to live in a community with multiple facilities. Further analysis and studies by others proved that race is the number one predictor of where toxic sites are located. For more than a decade environmental racism in the United States has been well-documented by NGOs, universities, and even the US government.6 However, the government has provided no effective remedies to the victims of these racist practices, nor has it taken effective action to stop such practices from occurring in the future. Examples of Environmental Racism in the United States

|

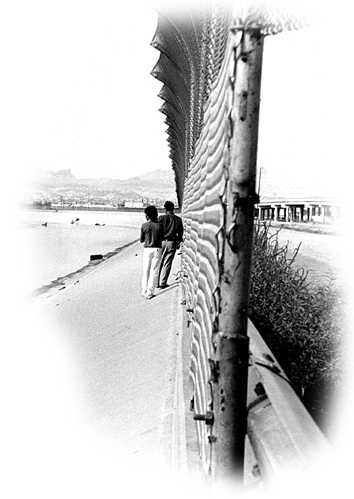

El Paso, US-Mexican border. Photo André Jacques, WCC |

Environmental Racism on a Global Scale Many have noted12 that there is a direct relationship between the increasing globalisation of the economy and environmental degradation of habitats and the living spaces for many of the world’s peoples. In many places where Black, minority, poor or Indigenous peoples live, oil, timber and minerals are extracted in such a way as to devastate eco-systems and destroy their culture and livelihood.13 Waste from both high- and low-tech industries, much of it toxic, has polluted groundwater, soil and the atmosphere. The globalisation of the chemical industry is increasing the levels of persistent organic pollutants, such as dioxin, in the environment. Further, the mobility of corporations has made it possible for them to seek the greatest profit, the least government and environmental regulations, and the best tax incentives, anywhere in the world. The destructive effects of environmental racism, therefore, are not exclusive to the United States. "Racism and globalisation come together in the environment, with the phenomenon referred to as 'global environmental racism' - a manifestation of a policy which has found domestic expression in countries like the United States, but which also has a global dimension."14 Environmental racism, although not new, is a recent example of the historical double standard as to what is acceptable in certain communities, villages or cities and not in others. One example of this double standard is the environmentally devastating method of extraction of natural resources, utilised by multinational corporations in developing countries. This has been the case with the Ogoni and other peoples of the Niger Delta in Nigeria, the U’wa people of Northeast Columbia, the Amungme of West Papua, Indonesia, the Indigenous People of Burma, and numerous others.

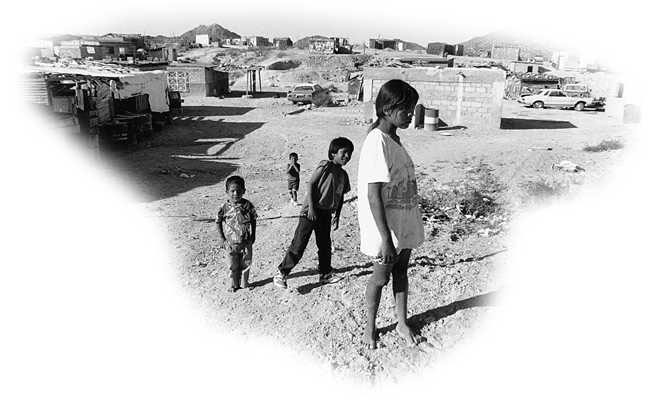

Other Examples of Environmental Racism from a Global Perspective |

Leaking oil from Shell oilfields, Nigeria |

|

US-Mexican border near El Paso. Photo: Peter Williams, WCC

|

Why is this happening?

What can be done? Globalisation from below is based on a global civil society that seeks to extend ideas of moral, legal and environmental accountability to those now acting on behalf of the state, market and media. Others have noted the need for transborder alliances20 , a global civil society21 and global social movements22. It is clear that global networking and global resistance are necessary strategies to solve the problems of environmental racism. The United Nations World Conference Against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance (WCR) in 2001 will examine contemporary manifestations of racism and strategies to achieve full and effective equality. This conference, and the preparatory processes that lead up to it, provide an excellent opportunity to highlight examples of environmental racism globally, develop global networks of organisations involved in environmental and economic justice advocacy, and begin developing strategies of mutual solidarity actions. The Regional PrepComs organised by the United Nations, and those being organised by the World Council of Churches, will enable people to make links on a regional level. The issue of environmental racism must be taken up at these regional PrepComs and its inclusion on the agenda of the World Conference must be stressed. Environmental racism is just old wine in a new bottle. It is essential that this issue be addressed seriously at the World Conference in 2001, that both domestic and international remedies for victims of environmental racism be identified, and that the Programme of Action that will be agreed to by member states includes concrete measures to ensure environmental justice for all. Dr Deborah Robinson was formerly a member of the Programme to Combat Racism team of the WCC. She is currently the Executive Director of International Possibilities Unlimited in Washington DC. She is also the co-chair of the International Committee of the Interim National Black Environmental and Economic Justice Coordinating Committee and is working to facilitate the participation of that body and other NGOs in the UN World Conference Against Racism. |

Photo: Leigh Lewis, Greenpeace |

Notes:

1. Benjamin Chavis, The Historical Significance and Challenges of the First National People of Colour Environmental Leadership Summit, in Proceedings of the First National People of Colour Environmental Leadership Summit (Washington, DC: United Church of Christ Commission for Racial Justice, 1991). |