The Earth as Mother

INDIGENOUS SPIRITUALITY

Aymara spirituality:

a challenge for Christian spirituality

By Rev. Humberto Ramos Salazar

The Earth as Mother |

INDIGENOUS SPIRITUALITY

Aymara spirituality:

By Rev. Humberto Ramos Salazar |

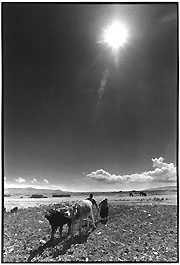

The Aymara vision of the cosmos is based on the notion of the binary, of complementarity

Clotilde Masabeyezu, Batwa

|

Let me set the context. The Christian church came to the Andean region in 1532 at the time of the conquest led by Francisco Pizarro. Since then there has been both the "Christian religion" and "ancestral religion". Because the Christian message was only partly understood by those who brought the Christian religion to the region, serious conflicts arose 1, costing the lives of millions of the Indigenous People of Abya Yala. This misinterpretation no doubt persists even today in certain parts of the Christian church, both Roman Catholic and Protestant, causing a division between "Christian" and "ancestral" understanding in religious matters and in the daily life of faith in "God". Aymara Spirituality When we speak of spirituality, we refer to the "ruah" of the Old Testament Hebrew texts or the "pneuma" of the New Testament texts. A certain conflict arises when I use the terms for spirit in the Aymara language : "kamasa" or "ajayu". In Aymara spirituality, the words "kamasa" or "ajayu" -- spirit -- is the force of life itself; the force that gives life, the force that permits communion, that creates hope, that enables you to go forward into the future. It is the force that compels you to confront the signs of death, strength in times of weakness, renewed, eternal life ("wiñay jacaña"). Aymara spirituality can be seen in the praxis of the people 2, it is expressed in everyday life. It is the expression of solidarity, it is communion with the whole creation, the very life of the people with their successes and failures, weaknesses and strengths, their plans and their hopes. Aymara spirituality, paradoxically, is the strength that accepts death as natural. The Aymara people are not afraid of natural death. On the contrary they accept it as part of every day life, part of life itself 3. But on the other hand they resist it when death comes in an untimely fashion 4. Aymara spirituality is not manifested exclusively in the sacred (the religious), but also in the profane (the ordinary), the whole of life. Although the Aymara are known as melancholy, sharing, dialogue and, in a special way, celebration are an intrinsic part of their lives. No-one exists in the world alone, solitary life is the death of life. Their vision of the cosmos is based on the notion of the binary 5, of complementarity, of living in function of others and not of oneself. In their world, the neighbour, nature (animal, vegetable and mineral kingdom) and the Supreme Being are conceived of as the others with whom they seek to live in balance and harmony. Every being, animate or inanimate, has its complement. The human being (jaqi) is complete and an integral part of the community when s/he has formed a couple (man -- woman = chacha-warmi). The jaqi is the image of the Supreme Being, the jaqi represents life. Understanding Aymara spirituality as constantly renewed life 6, we must now describe how it is expressed. I have often wondered how the Aymara people have still maintained their identity through the centuries and have been amazed at their capacity to integrate elements of the other -- the different, giving them new meanings, reinterpreting their world, without losing the essential of their own being, their spirit. One of the most striking examples is the festival of "alasita" 7. This socio-religious-cultural activity involves in miniature all the elements that a human being needs in his or her daily life, from the essential items in the family food basket (milk, bread, cereals, etc.) to the superfluous (a Toyota truck). Initially in the alasitas all the elements of daily life were present. Year by year, with the progress of technology, new items were included -- computers, micro-waves, cell phones, etc. -- showing that the Aymara vision of the cosmos was taking account of the modern world, reinterpreting values and resituating itself in the global context. Language is essential in any culture, for it is through language that the spirit and essence of cultures are expressed. The Aymara have preserved their language, which is rich in content and capable of describing both objects and actions in a very specific way. In the Aymara language, topography and cardinal direction can be precisely defined and various actions that would require a longer explanation in Spanish can be defined in a single term 8. Solidarity is inherent in the spirit of the Aymara. Interaction within the community is the normal course of Aymara life and community as such de-velops on the basis of solidarity. When each person is capable of caring for others and trusting others 9, this reciprocity makes the community one body. This solidarity exists in everything, from the smallest to the largest. Festivity and celebration are characteristic of the spirituality of the Aymara world. Spaces for encounter and relations with others are highly valued. Every event is an opportunity for celebration, from the birth of a new being to the death of a loved one. Communal work, labour on community tasks is a joyous occasion for those taking part. The sweat of toil mingles with satirical anecdotes about daily life which have the workers roaring with laughter. A community that does not celebrate is a dead one. Religiosity is part of the Aymara’s very being. The Aymara conceive of the Supreme Being as the creator of all things, everything was made by God -- what we can see and feel and what we cannot see and cannot feel (the unknown). Because they recognize God as the supreme maker of the creation the Aymara are profoundly religious. A religious sense is expressed in different ways in everyday life, from constant thanksgiving to remorse and repentance for any harm they have done. In their view of the cosmos the Aymara find God revealed in all creation (without falling into pantheism), in all that generates life and enables community. Natural phenomena which destroy life are understood as coming from God, as a warning or revelation to make them stop and think or to correct errors. In this sense, the Aymara never feel alone, they believe that God goes with them wherever they are and wherever they go. With this inherent sense of the religious, waking up in the morning is proof of the existence of God who allows the human being to see a new day, to see the plants growing. To see the arid land of the Altiplano gradually covered in green is to feel the presence of God. Gratitude and respect are a fundamental part of the religiosity of the Aymara world. A proud or arrogant attitude is condemned by the community as disrespectful of the Supreme Being who causes the dawn to break and the sun to set in the evening. Giving thanks as they eat; praying for the whole wide world that God will provide the daily food for all expresses their gratitude to God for the food they have and an attitude of love towards their neighbour. There is community prayer as seeds are planted in the soil, asking God to make them flourish and bear fruit, acknowledging God in his infinite goodness. Penitence and forgiveness are not just a personal affair, they also concerns the whole community. For this reason the authorities (jilaqatas or mallkus) call a meeting every year on the day of penitence and forgiveness. It starts with a communal meal primarily given over to quiet reflection; it continues with forgiveness -- forgiveness asked of God for actions and thoughts, then of all the members of the community from the oldest to the youngest, asking forgiveness even for actions that harmed animals, plants and the natural world which God has given us to care for and live in. Penitence and forgiveness culminate in a celebration, in the firm belief that God hears such pleas and true repentance. |

Richard Louse P. Bagayao, Igorot

Tomo Kawaguchi, Ainu |

Christian spirituality Since this is a reflection in an Aymara-Christian perspective, I should also refer to Christian spirituality. I prefer to continue with the concept of "ruah" mentioned at the beginning of this article because it comes closer to the Aymara understanding of the world; taking the texts of En 1:2, "and the Spirit of God moved over the face of the waters ..." and Gen 2:7 "Then the Lord God formed man from the dust of the ground and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and the man became a living being." These two texts speak to us of the beginning of the creation both of the world and of humankind. Both show that the Spirit of God is the source of life: in the first case a force flows through the creation establishing order and in the second man is created by God. We find the continuity of this central thought in Lk 4:18 ff: "The Spirit of the Lord is upon me because he as anoin-ted me to bring good news to the poor ..." "Spirituality" is thus to be understood as the expression of the Spirit of God in our lives. The (Christian) church links spirituality with the dogmatics of ecclesiology, in relation to the third person of the Trinity: God the Father, Son and Holy Spirit. In this sense there is a link with the coming of the Holy Spirit which gives rise to the first church community, as told in Acts 2. In my understanding, however, the Spirit of God or the Holy Spirit mentioned in the New Testament is not a force that is revealed only in churches or to people gathered on Sundays. Spirituality is the revelation of God in our most intimate being; it is our daily living experience of our faith in Jesus Christ, our Lord and saviour, who came to overcome death and will come again in glory. Faith which sets us free to be messengers of the good news to our neighbours, building the Kingdom of God in the community of those who love life and seeking to give others the hope we are shown in Rev. 21:1ff: "See, the home of God is among mortals. He will dwell with them as their God; they will be his peoples, and God himself will be with them; he will wipe every tear from their eyes. Death will be no more ...." A message of hope in the midst of despair, in moments when we think God has abandoned us. Christian communities rejoice in the God of life as they reflect on the Word, sharing their faith and strengthening one another through common projects that lay the foundations for life. Spirituality is the intimate living experience of our faith in Jesus Christ, in the God of our ancestors, Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. It is living our daily lives with constant a point of reference (our north), which are projects that promote life in face of the signs of death. Conclusion I shall conclude with the controversy concerning the absolute claim of Christianity. What has been said about Aymara spirituality and Christian spirituality shows clearly that the absolute claim of Christianity has been overcome, and it is "legitimate" to be an indigenous Christian. Indigenous spirituality concentrates on living a full life in relation with the whole creation, as a commandment from God himself. We find the same form in the Bible, for this is the commandment given to Christians by the "God of Scripture". Consequently, there are no points of contradiction or opposition. On the contrary, the two are complementary and they enable Indigenous People (Aymara) who have chosen to follow Jesus Christ to live their spirituality in a human and dignified way, avoiding conflicts of identity and denial of their sense of self. Trusting in the power of God at work in all cultures and showing itself in different ways, we live out our faith day by day in the God who is the God of History and the God of life. Humberto Ramos Salazar is a Bolivian Aymara. He is a member and pastor of the Lutheran church. He did his theological studies in Buenos Aires (ISEDET) and most of his work has been done in ecumenical institutions. GLOSSARY:

|