2000: The year in review

Sharing alternatives to economic globalization

Sharing alternatives to economic globalization

The debate came to public attention especially in connection with “Geneva 2000”. This gathering, held 26-30 June, was the United Nations General Assembly’s Special Session on Social Development, a follow-up to the World Summit on Social Development held in Copenhagen five years earlier.

An ecumenical team in New York, coordinated by the UN office of the WCC and the Lutheran World Federation (LWF), had been following preparations for this meeting for some years. In 2000 the team attended both the February and April sessions of the UN’s preparatory committee — prepcoms — leading up to Geneva 2000, also called Copenhagen plus five.

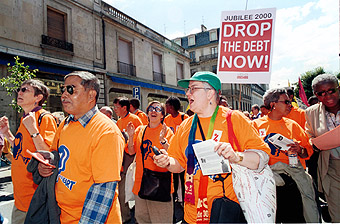

Gail Lerner, the WCC’s UN representative in New York, said that in selecting team members “we gave priority to the South, to women and to Indigenous People”, who have an expertise based on “lived experience”. Members of this team appealed for a change of heart by those dominating the world’s economy, and advocated specific measures such as cancellation of debt and adoption of a proposal

Hope persisted that Geneva 2000 might bring some progress. “I would like the declarations coming out of Geneva to move from the language of encouraging government action to more binding language,” said an ecumenical team member from Mozambique, Methodist Bishop Bernardino Mandlate. “I would like to see target dates, a monitoring process and greater involvement of civil society.”

However, the team’s hopes were dashed for the most part, and they found the sessions in Geneva marked by even less understanding and commitment than was seen at Copenhagen. Kofi Annan, UN secretary general, was present at a church service attended by representatives of other faiths at Geneva’s St Pierre cathedral. During the service, there were calls for a more just economic system that recognizes the worth of every one of God’s people. But later, WCC team members and representatives of many other non-governmental organizations were dismayed to find him endorsing the position of the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development in his report, A Better World for All.

The report was issued on the opening day of Geneva 2000. Two days later, WCC general secretary Konrad Raiser sent Annan a letter, released to the press, reporting “great astonishment, disappointment and even anger” among many representatives of civil society. Annan had participated in “a propaganda exercise for international finance institutions whose policies are widely held to be at the root of many of the most grave social problems facing the poor”, Raiser said.

He said Annan had “cast doubt upon the will of the United Nations to reaffirm the Copenhagen commitments,” and was endorsing an approach that “could further limit space for governments and civil society to develop alternative goals and means to achieving social development”. Annan’s willingness to put the UN on a partnership level with financial institutions controlled by a few highly industrialized countries damaged “the credibility of the UN as the last real hope of the victims of globalization”, the WCC leader said.

The WCC, itself a global body committed to developing a sense of global community, does not oppose a global outlook as such, or support nationalism against a global perspective. It has member churches in every part of the world, its staff travelled throughout 2000 to strengthen the global solidarity of the churches, and its offices in Geneva welcomed more than 5000 visitors from nations far and wide during the year, a significant increase from a previous average of 3600. But the WCC questions the neo-liberal globalization concept expressed by the dominant economic powers. From the perspective of the WCC and its concern for those living in poverty, the policies of the Bretton Woods institutions and the World Trade Organization have “not only failed to bridge the gap between rich and poor and achieve greater equality, but rather contributed to a widening gap”. These policies, relying heavily on market forces, have virtually excluded the poor from any voice in social development or their own future, and have brought social disintegration rather than development, the WCC contends.

John Langmore, director of the UN’s Division of Social Development which helped prepare for Geneva 2000, encouraged the churches to “keep on arguing for the vision”. An Anglican from Australia and, incidentally, a member of the WCC’s Commission of the Churches on International Affairs (CCIA), he said a “market fundamentalism” that sees all problems answered by free markets stands at odds with the biblical concept of social justice.

Raiser’s letter, which included a reiteration of the WCC’s commitment to the goals of the UN and personal support for Annan in other contexts, was taken seriously, and stimulated the UN secretary general to reply. The report expressed “UN objectives and UN targets”, Annan insisted. So in Geneva, the issue remained unresolved.

Looking back, Raiser says his critique of Annan produced “an unexpectedly wide echo”. One surprising result, he says, was a decision by officials of the International Monetary Fund to seek a meeting to discuss the points at issue with WCC leaders, a request that was granted. The discussion is likely to continue, Raiser says.

Sam Kobia, director of the WCC Cluster on Issues and Themes, says “globalization”, as carried out by the ruling economic forces, has an ideological thrust, conveying certain values, and is not a neutral, inevitable force. Its values are competition and unlimited consumption, and it has a logic of homogenization, he says. The ecumenical movement must continue to offer “an alternative logic” of a unity of the world’s people that is based on sharing, justice, solidarity and diversity, the WCC official says.

Globalization is a force that over-rides the interests of local areas, cultural as well as financial. Even national governments can be overwhelmed by the economic force of globalization. In the interest of free trade, they are pressured to let international corporations operate unimpeded, even if the nations’ own businesses and social structures are smothered in the process.

The WCC has followed and supported the UN in many ways throughout the years the two bodies have existed, and in June the CCIA, which has held consultative status with the UN Economic and Social Council from the earliest days, got this status raised from the second to the top - “general” - level.

In other actions, the WCC sponsored hearings in Bangkok and Seoul on the impact of economic globalization, particularly in relation to the financial crisis that had devastated much of the economic life of Asia. Two dossiers on alternatives to economic globalization were published. And the WCC joined with the Lutheran World Federation (LWF), World Alliance of Reformed Churches (WARC), World Student Christian Federation (WSCF), Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA), Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) and Frontier Internship in Mission (FIM) to form an Ecumenical Coalition for Alternatives to Globalization.

Economic globalization was also one of the foci in November, when the WCC’s Asia and Pacific desks hosted a joint meeting of both regional ecumenical groups in Shanghai and Nanjing with the Christian Conference of Asia and the China Christian Council. Participants tried to set an overall ecumenical agenda for the region and reflected on the role of the churches in a China moving from a socialist system to a market economy in a globalized system. Matthews George Chunakara, WCC executive secretary for Asia, said Asians are concerned about foreign businesses that “drain natural resources from developing countries”.

Even when globalization is not the central focus it can emerge as a problem in discussions on other issues. The WCC has sought to deal with Christian-Muslim tensions found in many parts of the world, and has participated in dialogue sessions such as one in Beirut in March and one in Cyprus in June. But when it brought church leaders from Indonesia, Pakistan, Ghana, Nigeria, Sierra Leone and Sudan together for reflection on how to deal with religious intolerance, they reported that Christians are often blamed for globalization, which is viewed in those countries as a form of recolonization by the Christian West.

An area where unrestricted economic forces present a moral as well as economic challenge is global warming. The WCC has shown its concern for this issue by following developments regarding the UN Convention on Climate Change.

When the Conference of Parties to the convention held their sixth session in The Hague, Netherlands, in November, the WCC led in arranging an inter-religious service. The Council also brought an ecumenical delegation to follow developments. Marijke van Duin, a WCC representative from the Netherlands, said the challenge is to take small practical steps without losing sight of the broader vision. “You can work for life or for death,” said another WCC representative, Jessie Mugambi of Kenya. “We in the WCC have opted for life.”