by Shyamala Ariarajah

| Introduction The concern to address the economic injustices and humiliation confronted by the poor within interdependent economies has been the main driving force for ethical responses in the financial system. These responses often took the form of a variety of financial instruments at the local, national and global levels. Despite numerous ethical interventions over the last thirty years, each successive wave of economic crisis and the consequent hardships genera-ted by it for the poor and poorer nations have been more severe than the previous ones. The persisting current social and environmental crises, known as the negative effects of economic globalisation, are increasingly understood as a consequence of the policies or conditions attached to both lending and grant-making to both for-profit and non-profit organisations within the inequitable operating framework of the global economy. In other words, the unfair economic divide between hard and soft currencies, on which the post-war global economic and financial systems were founded, continues to perpetrate waves of global poverty. In such an unequal operating framework, the commercial models of asset allocation or financing instruments, which focus merely on short-term financial objectives, further increase the social and economic disparities within and between nations. These disparities generate insecurities and thereby disrupt social cohesion and global peace. The Kairos Investment Fund (KIF) is a new model of a financial instrument that was developed to apply a new investment ethic within contemporary financial systems. The present article is a brief overview of why and how the KIF seeks to complement other ethical interventions that seek to bring justice at local, national, and global levels within the current financial systems in which investments operate. Motivation and purpose Developments within financial systems

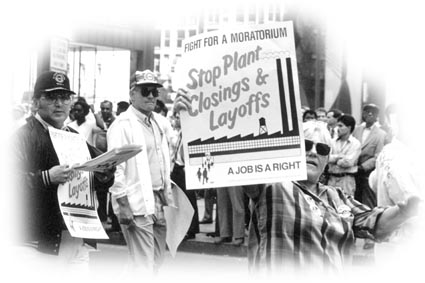

Understanding the systemic crisis From the perspective of the business sector, the continuous restructuring of multinational corporations through relocations, cross-border mergers and acquisitions aimed merely at increased market shares not only threatens to revert the financial system back to monopolistic or undemocratic corporate practices, but also lead to a re-colonisation process. The mass layoffs that accompany such restructuring reduce the capacity of consumers to buy the products and services that these companies offer, and thereby contribute to enormous losses of revenue, leading to their own bankruptcies. These bankruptcies induce the economic downturn of a series of other small- and medium-size companies and institutions, including the investment banks that finance their equity capital and loan structure. However, while the multinational corporations are able to obtain creditors’ protection and more financing from their governments with taxpayers’ money during further downsizing operations, many small- and medium-size companies and institutions are forced out of business for the lack of such privileges. From the individual’s perspective, this kind of market expansion not only brings job loss but also loss of lifetime savings, because of the pension funds, insurance policies and savings bank accounts invested through investment banks in these multinational corporations. The social insecurity, economic hardship and humiliation generated by these losses induce a variety of cycles of violence throughout the world. Double exclusion Unjust loss of creditworthiness Above all, the loss of value of the local currencies prevents people in soft-currency countries from re-paying loans from both private and public investors in the hard-currency countries. Such an unjust way of losing credit worthiness and jobs result in a dual loss of dignity. In this context, when country credit rating agencies downgrade the soft-currency countries, foreign investors and fund managers withdraw their investment capital with a warning that classifies the soft-currency countries as high-risk countries. However, this incapacity to re-pay loans and a reduced capacity to buy the goods from hard-currency countries doubles negative effects for people in hard-currency countries: the consequent increase of unemployment and economic disparities within hard-currency countries jump-starts a new wave of social instability, violence and financial systemic crisis. The speculative investment trends that flourish in this climate of increasing currency gap contribute to deepen the next wave of crisis, and to increase poverty. This explains why this ever-increasing currency gap – which continuously reinforces the inequitable founding basis of the global financial system – continuously frustrates the goals of humanitarian missions. The expected benefits for both hard- and soft-currency countries from re-locating multinational corporations’ production and service units in soft-currency countries have been far outweighed by the negative effects of this one-way liberalisation process. Thus current poverty eradication programmes and prevalent ethical interventions need to be complemented by new ethical responses that focus specifically on addressing the global poverty perpetrated by the double exclusion of the soft-currency countries from the global economy. The concern to address current economic injustices within both hard- and soft-currency countries perpetrated by the increasing currency gap, is expressed in the search for a new investment ethic. The search for an investment ethic The essence of the new investment-ethic If ethical criteria are based on the principle of justice, it follows that one person or community cannot unilaterally determine what is just or fair without taking into consideration the opinions of all parties concerned, including those affected by investment decisions. It also means that, within an inequitable systemic framework of hard- and soft-currencies, what is ethical cannot be decided on the basis of speculation or simplistic assumptions about different countries and peoples. This leads to the conclusion that investment decisions, insofar as they affect peoples’ lives, have a strong relatio-nal dimension; what is ethical in the area of investments can only be determined on the bases of the priority of investment needs and of consultative processes with the three main protagonists of the financial systems. These protagonists are: the investors, the companies or institutions that benefit from investments (security issuers), and those affected by investment decisions. Such a consultative process of decision-making, known as discursive-ethic, is conducted in a transparent way and enables us to identify injustices and introduce correctives; it also induces a transformation from speculation to consultation in the financial systems in which investments operate. Above all, it has the potential to ensure the equitable participation of both hard- and soft-currency countries within the global economy and thereby to democratise contemporary financial systems. It is this double-shift from speculation to consultation, and from domination to equitable participation within the interdependent financial systems that is at the heart of the new investment ethic. Features of the financial instrument • the ethical objective is to contribute to the evolution of a people-centred financial system in which there is equality of access to opportunities and information for all; • the financial objective is to provide its investors with a financial return similar to that of a global mixed portfolio investment fund through middle- to long-term capital appreciation. The priority of needs of investments within each country compartment of the fund is determined through the above-mentioned consultative process, in view of democratising financial systems. However, the portfolio construction of the fund is conducted through an ethically coherent and scientifically logical asset allocation model based on three main ethical criteria: shared responsibility, shared risk, and shared return between hard- and soft-currency countries. Various indicators related to purchasing power parity and human development, are used to translate these criteria in constructing the model. The ethical criteria for asset allocation within each country compartment takes into account the following four dimensions: 1. the priorities of both infrastructure and employment creation needs of each country; 2. the distinct roles and responsibilities of the three main economic actors, namely, the government, business and third sectors; 3. the development of small- and medium-size local companies and institutions within each country; 4. the investment in the three main asset classes (shares, bonds and cash). Security issuers within each country compartment of the fund are selected on the bases of responsible social and environmental practices, responsible management of financial resources of companies and institutions, and transparency of information disclosure. The portfolio construction procedure aims at optimising the allocation of both natural and human resources. |

|

| A critical support organisation The requirement for a consultative mode of decision-making to implement the new investment ethic has led to the formation of the Kairos Global Association for Investment Ethic as a critical support organisation of the Kairos Investment Fund. It is a non-profit non-governmental organisation, which aims at linking lenders and borrowers within a common ethical framework. It seeks to alter the speculative investment trend through a wide and sustained educational process in collaboration with justice-oriented organisations. |

Young girls stitching footballs in Pakistan Sialkot, Pakistan © ILO |

| The education process will be driven by the findings of ongoing diagnostic research on the role of the contemporary lending and borrowing system (i.e.: the financial system) in increasingly monetised economies. Through this process, it seeks to build trust between for-profit and non-profit organisations and, between hard- and soft-currency countries by soliciting cooperation to sustain social cohesion and global peace. Launching the advocacy campaign and the fund Ms Shyamala Ariarajah is director of the Kairos Global Association for Investment Ethic based in Geneva, Switzerland. |

|