THE VIOLENCE OF GLOBALISATION

By Yash Tandon

|

THE VIOLENCE OF GLOBALISATION

By Yash Tandon |

| Even as its proponents speak of increased prosperity and investment confidence, the process of globalisation breeds violence and conflict when it continues to produce inequality, poverty, environmental destruction and unprecedented concentration of economic power for a few while the majority are marginalised and excluded. Africa is a victim of this sad phenomenon of globalisation. The cumulative adverse effects of globalisation on Africa require careful and deep analysis which go beyond the contemporary dominant ideology of the free market and the "blame the victim" syndrome. ECHOES asked Professor Tandon to look at the issue of the violence produced by the processes of globalisation, using Africa as a case study. | On causes of conflict and violence, there are two major lines of thought. The mainstream or dominant theory tends to emphasise the internal factors within a nation as the root causes. These have to do with lack of economic growth on the one hand, and poor governance on the other. The corresponding solutions are economic growth and good governance. Whilst there is much that may be accepted in this analysis, its principal fault is that it does not adequately analyse the international, or global, dimension of the conflicts, and it does not connect various factors in an holistic manner. This is so because of its stake in the preservation of the existing system. Thus, the very factors that have impoverished a region - namely exploitation by foreign capital under conditions of free market - are the ones offered by mainstream thinkers as solutions to that regionís economic woes. The alternative perspective reasons that while poverty is at the root of conflict and violence, it does not simply exist but is created by the manner in which a region is integrated into the global economy. The basis of this integration is the unequal exchange between what the region contributes to the global economy and what it gets in return. This is legitimated by the ideology of the free market, but behind the free market are big monopolies and oligopolies that control the markets - from diamonds to beef to Microsoft software. The free market is a myth. The violence is rooted in the regionís continued impoverishment by the system. Mainstream Thinking on Peace and Conflict in Africa Mainstream ideas on the structural causes of conflicts in Africa presented by the World Bank and the IMF1 could be the first place to start with analysing these ideas. However, the World Bank/IMF ideologists are easy targets these days, and so, to give the mainstream ideas a fair chance, we rather take up for examination the views of the Secretary-General of the United Nations, Kofi Annan. As an African who was actually involved in conflict resolution in Africa - Somalia and Angola, for example - he is singularly qualified to address this issue. What makes his thinking significant is that he has to balance the ideas of the dominant Bretton Woods institutions with those of the developing countries which constitute the numerical majority of the UNís membership. Of course, he cannot afford to stray too far from the dominant set of ideas or he would not be there in the first place. |

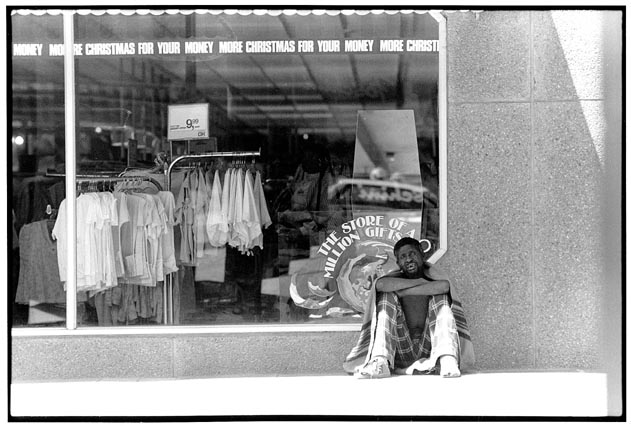

Photo: Peter Williams/WCC |

This balancing of ideas between World Bank/IMF type of hard core thinking and that of the third world states, is not done consciously. It is embedded in the history and culture of the UN itself. The Secretary-General then becomes the carrier of these ideas; he institutionalises them. It is important to understand this context not only because this helps us to understand why the Secretary-General is saying what he is on peace and conflict in Africa, but also because it helps us to avoid raising unnecessary questions, such as why the UN did not play as aggressive a role in Angola as NATO did in Kosovo, for example. Let us start with the external or international dimension first. The easiest entry point here is the economic sector. Take the debt issue, for instance. The Secretary-Generalís facts about the debt burden are generally accurate. In 1995, he says, Africaís external debt totalled $328.9 billion - of which approximately 45 per cent was owed to official bilateral sources, 30 per cent to official multilateral sources, and 25 per cent to commercial lenders. To service this debt fully, African countries would have had to pay to donors and external commercial lenders more than 60 per cent ($86.3 billion) of the $142.3 billion in revenues generated from their exports. In fact, African countries as a whole actually paid more than 17 per cent ($25.4 billion) of their total export earnings to donors and external commercial lenders, leaving a total of $60.9 billion in unpaid accumulated arrears. In other words, Africa could not even service its debts; it paid $25.4 billion of the $86.3 billion of the interest it owed to its creditors. Thus, instead of reducing the debt stock it actually increased by a further $60.9 billion. The debt goes on piling year after year. Why do the creditors appear to be satisfied with receiving only about a third of the interest owed to them on past debt? One explanation is that they cannot afford to ruin the potential market in Africa for their goods and for their future investments, which is what would happen if they forced Africa to make the debt payments in full. To deal with this situation, the IMF has created a concept of sustainable debt, i.e., debt that can be paid out without ruining the economy. It is the same thing, really, as sustainable poverty: keeping poverty in Africa at a level where people do not actually fall down dead. In the case of Mozambique, to illustrate the point, sustainable debt means letting Mozambique pay a certain portion of its export earnings so that it continues to import at least something from the rest of the world. By going easy on Mozambique this way, the creditors create the illusion that they are being nice to Mozambique. But all the time the debt noose is tightening around its neck because it is getting bigger and bigger simply through interest arrears. The creditors can use this debt noose then to impose a structural adjustment programme on the state, and to persuade it to keep the doors open to foreign goods and capital. |

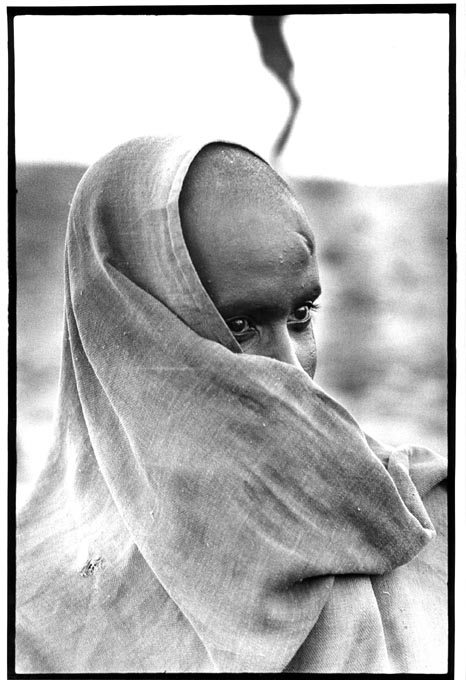

Photo: Sebastio Salgado, WCC |

Let us link this to the bigger picture. There are two important related questions: how did the debts arise in the first place, and why very little is in fact done to remove this formidable barrier to Africaís development when it is generally recognised that without removing the debt burden there is no hope for development in Africa? These questions become important when we make the link between debt and economic development, and between lack of economic growth and conflict: we can argue that one of the significant causes of conflict in Africa is the struggle for survival in a situation of scarce resources. The debt imposes severe strain on these resources. This struggle for resources manifests itself in the struggle for state power. Further, given the historical division between ethnic groups in Africa (exacerbated during the colonial rule, as in Rwanda, for example), the conflict can trigger civil war and even genocide. Here we have one root cause of conflicts in Africa. The debt carries a heavy responsibility for civil strife and war in Africa; its cancellation can be a major move to sustainable development and peace in Africa. However, it is not in the rule of the game of global financing to simply write off debts because such a move can have serious systemic consequences. Also, even if debts were written off today, they would spiral up again given the inherently unequal economic relations between Africa and the industrialised world. Of course, every aspect of conflict and peace cannot be pinned down to debt. Complex matters cannot be reduced to single factors. But given the linked nature of all these factors, it is difficult to separate the significance of one factor from that of others. The principal reason of debt is unequal trade relations between Africa and the rich countries. None of these issues is explored in the Secretary-Generalís report. The reason for this apparent oversight is that in the dominant discourse, these systemic causes of debt cannot be revealed; they could de-legitimate the system itself, and thus its survival. It is far easier to offer technical solutions such as the HIPC (Heavily Indebted Poor Countries) initiative, that seeks to write off part of the debt in return for certain binding commitments, than to raise political issues which put into question the whole system of Africaís exploitation by the industrialised countries. This is what we mean by the partial nature of the mainstream discourse on the causes of Africaís conflicts. Even the UN, let alone hard-core institutions like the World Bank and the IMF, cannot afford to tell the whole truth about debt. Of course Africaís debts have many complex political and economic causes. Take the debts left by Mobutu in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, or those left by the apartheid regime in South Africa. Everybody now accuses Mobutu of corruption and bad governance. With better use of borrowed money and with a more accountable system of governance, the country should not have had to face the present problem of debt. But the real question is: why did the rich countries go on putting money into Mobutuís coffers in full knowledge of his corruption and undemocratic governance? Why was it not an issue before, and why now? Much is made in mainstream discourse about mismanagement of borrowed funds. Connected to this is the inability or incapacity of civil society to make governments accountable for the use of these funds. But the point is that whilst all these factors are relevant, and linked, why were they not raised in earlier times, and why now? Mismanagement and corruption aside, the truth has to be faced that the most significant reason for the debt is unequal trade relations between Africa and the industrialised countries. There is a structured, or systemic, relationship between the products expor-ted by Africa and those imported that ensures that Africa has to go on producing more and more of the same to get less and less of the imports from the rich countries. The fact of the matter is that Africa is weak and impoverished because its rich natural resources are taken away from the continent at a fraction of their value. The terms of exchange between Africaís natural resources and the Westís capital-and-knowledge intensive technologies continue to remain the basis for vast seepage of net value out of Africa and into Europe, the USA and Japan. In other words, a no win situation for Africa is embedded within the system itself. We are saying nothing new, of course. Nyerere drew attention to this in the 1960s, and 30-40 years down the road, it continues to be the most significant factor of Africaís sustained impoverishment. To ask why some East Asian countries were able to get out of this vicious circle of poverty opens up a different debate. One explanation is that Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, Singapore and Hong Kong were deliberately encouraged, and assisted, by the USA to build their economic infrastructure to fight against communism. Japan later helped the second-tier countries such as Malaysia and Thailand to industrialise. These developments were thus a product of the cold war. Now that it is over, the West is systematically rolling back the gains these countries made. In the aftermath of the East Asian financial meltdown, starting with Thailand in August 1997, the West has reasserted its control over the banking, financial and industrial power centres in South Korea, Indonesia and Thailand. Even Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan and Japan are no longer protec-ted from mergers and take-overs by Western corporations. Only China is resisting this renewed aggression by the West, though there is some doubt whether it can hold on for long. The point is that it is no longer possible to point to the South East Asian economies as models of a successful break from the dominant control of the powerful countries of the West.2 We took the issue of the debt only as an example. The same kind of analysis can be applied to any of the other elements in mainstream discourse. For example, who can dispute the importance of the rule of law, or the need to have governments accountable to the people - elements which the Secretary-Generalís report says are important for establishing the basis for an enduring peace in Africa? Of course, these aspects of good governance are important for Africa. They are important not because the West now includes these as part of the conditionalities for aid to Africa, but because Africans also value life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, just like anybody else. Transforming The Culture Of Violence Why do conflicts degenerate into spasms of uncontrolled violence that defies all canons of humanity, wisdom and tolerance? We have seen human carnage in many conflict-situations in Africa - Rwanda, Somalia, Liberia, Sierra Leone, the DRC, to name a few. Erstwhile friends become overnight enemies; neighbours kill each other with machetes; families split along ethnic lines. In Rwanda alone, in a matter of 100 days, about a million people were massacred - a scale of killings that is almost unpreceden-ted in world history. So even if there are good reasons for conflicts, there are no good reasons why these conflicts degenerate into violence and brutality that shame humanity. Why do these things happen? We are not competent to go into the group psychology where some of the answers to this perplexing phenomenon must lie. What we can offer are some ideas on how to move forward in this complex area. Gandhiís answer to violence was not to offer counter-violence, but to sublimate it by offering oneself as willing victims of violence and overcoming it with soul force (satyagraha). Whilst fighting against the British Raj, this strategy, despite occasional lapses, was remarkably successful. But when the partition came between India and Pakistan, all the lessons learnt from years of satyagraha could not stop the human carnage. Is it because in the struggle against the British, the people were fighting for satya (or truth) against a rule that had become immoral and unsustainable, whereas it was difficult to know where truth lay when it came to partition? Then everyone was for himself or for family or for religion. Truth lay, as it were, on both sides. But this still does not explain the sheer brutality or inhumanity of the violence. In our view, human nature has both evil and good aspects. It is the function of religions and spirituality to arouse the good against the evil, but religions have not proved to be dependable allies in the struggle against violence. If individual soul force becomes a spent force in times of inter-ethnic violence, and if religions are not dependable allies, then the only option left is to create institutional structures that can prevent conflicts from erupting into violence. We know, for example, that the Bahutu and the Watutsi in the pre-colonial period had complex institutional structures that not only enabled social mobility across class/caste lines but also across ethnic lines. We also know that the clan system in Somalia had complex structures that balanced the rights to grazing and water of different clans, and a system of disputes resolution that preserved the integrity of the clans as well as social peace.3 These structures were destroyed during the colonial period, and nothing viable put in their place except the authority of the colonial powers. So when this authority was removed at independence, there was nothing to fall back on by way of institutional checks and balances. So a short answer to the problem of violence is that we need to work at various levels - at the individual level with education as the key element; at group level where a culture of tolerance and mutual respect need to be consciously inculcated; but above all, at a national level where durable and credible institutions which balance the rights and responsibilities of groups (however defined) need to be put in place. Democratic institutions that balance rights and responsibilities and provide for the rule of law are tried and tested methods of resolving conflicts without resort to violence at the national level. But even here, we have discovered that the representative form of democracy that is practised in most Western countries cannot deal with other kinds of violence such as inter-state violence, or structural violence that is embedded in the economic system. Western democracies are hegemonious and too readily resort to violence and war against countries that do not conform to their order and authority. Also, structural violence as embedded in the free market system, of which Africa is victim, is something that, within the Western system of morality, is a permissible kind of violence. So the system of democracy developed by the West has many defects. We need to try other forms of democracy, such as participatory or communitarian forms. |

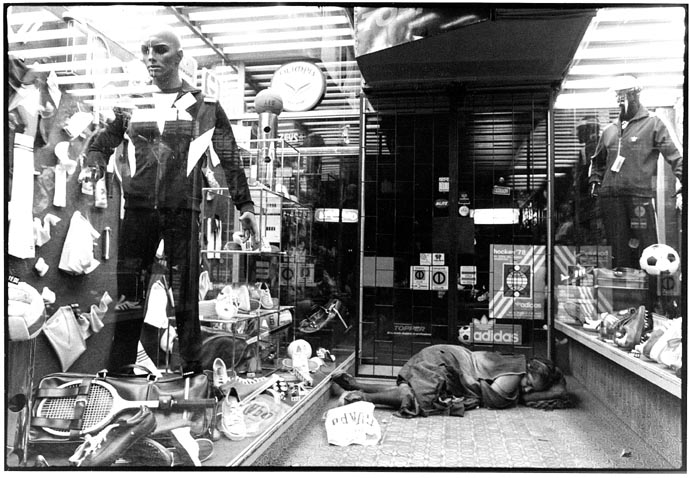

Photo: Sebastio Salgado |

Conclusions The issues of conflict and peace are central to all those who are concerned about the future of Africa. We have seen that over the years the nature of conflicts in Africa has changed. The anti-colonial wars and border conflicts have given way, by and large, to intra-state, or civil, wars. So what is to be done? Delinking from the system is not a viable or practical option for Africa. But there are ways in which Africa can partially de-link itself from the global market. Already the bulk of Africaís populations survive by their activities in the so-called informal market. This is not to glorify the informal sector, but to say that a condition of being de-linked is already a reality for millions in Africa. What is needed is a more concerted effort to strengthen those institutions and structures that are able to survive in a de-linked environment. A second line of defence for Africa is to re-negotiate its terms of integration into the global system. This the African governments will not do on their own because they are conditioned by the agreements they have entered into with the IMF, the World Bank, the WTO, and the donors, and by the specific interests of their elites. They may take action only when pressurised by the grassroots and community organisations. However, where governments have ceased to respond to the just demands of the people, the latter may have no choice but to resort to various forms of direct action in confronting their states. One issue on which direct action is called for immediately is the annulment of all debts owed by Africa to the rich nations. The various schemes offered by the Bretton Woods institutions (such as HIPC), and accepted by African governments, are mere palliatives that obscure the reality behind debt. What is needed is the transformation of both the economy and the nature of the state. The economy has to be brought back under the control of the people and reshaped to service primarily the needs of the people, and not those of the exporters of Africaís wealth. The kind of state that is needed is not the minimum state, much favoured by the IMF and the World Bank, but the responsible state. The minimum state leaves power in hands of corporations. What we need are states that can carry out their social responsibilities. The people need a state that can resist pressure from the WB/IMF, and donors one that can ensure food security, build self-reliance in industry, regulate strategic sectors to protect national sovereignty and economic stability, and enable the exploitation of natural resources by indigenous people first and foremost for their own benefit and then for export if necessary. We need to do away with a unitary, centralised, authoritarian state system; to encourage a political culture that recognises ethnic, linguistic and cultural differences; and to create conditions of natio-nal unity based on the fullest expression of these diversities. Beyond partial de-linking, and partial re-negotiations of the terms of integration into the world market, the people of Africa must sow the seeds of a new future based on imaginative alternative forms of production at the economic level and governance at the political level. This would include a new political culture of tolerance, and the creation of institutions that balance the rights of people with their responsibilities. Whilst it is impossible to return to the past, there are valuable insights that the past provides (such as the manner in which, in pre-colonial times, the people of Rwanda and of Somalia used to resolve conflicts amongst themselves), that could be the starting point for self-generated and endogenous institution-building. Only then will Africa move from violence to enduring peace with justice. Professor Yash Tandon, from Uganda, is an economist. He is presently Associate Research Fellow at the Zimbabwe Institute of Development Studies and Director of the Southern African Trade Information and Negotiations Initiative, which is a project of the International South Group Network and aims to help build Africaís capacity to take a more effective part in the global trading system.

Notes |