VIOLENCE IN THE CHURCH

By Lesley Orr Macdonald

"If it be your holy will, grant that a place of your abiding be continued still to be a sanctuary and a light"

|

VIOLENCE IN THE CHURCH

By Lesley Orr Macdonald

|

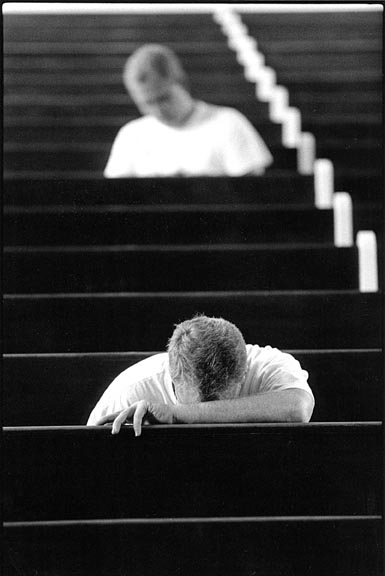

Photo: Jean-Claude Lejeune, WCC |

What does the word ‘church’ evoke for you? As a member of the ecumenical Iona Community, based in Scotland, these words (which form part of the daily worship of the Community) are deeply embedded in, and expressive of my faith and experience. They hold and carry a vision and a hope for the church of Christ on the tiny Scottish island of Iona, which for centuries has been experienced by countless people as a powerful place of encounter with God, of challenge and of peace. For me, as for so many others, Iona has truly been a sanctuary and a light. But the words of that prayer speak of more than a particular location, however resonant. In the midst of human struggle and passion and pain, in the heart of the common life, where are the places of God’s abiding? Is the church, embodied in diverse human communities, structures and institutions around the world, a sanctuary and a light? Here are some of the voices I have listened to for years: the voices of refugees who have had to flee from jeopardy, suffering and harm. They found no sanctuary in the Christian church, for the violence they suffered was perpetrated, legitimised and compounded in the heart of the church - by individuals and structures, attitudes and beliefs. Not just in Scotland, but all over the world. For too many victims and survivors of domestic and sexual violence, the community of the church has become an exclusion zone, as the Living Letters report of visits to the churches during the Ecumenical Decade of Churches in Solidarity with Women makes clear 1. A sanctuary of care? I’m angry because the sexual abuse destroyed my self-esteem. I hated that experience of being used and discarded. The clergy should be CAREFUL with people. Playing with the bodies and souls of vulnerable folk is all wrong, and that carelessness is so hurtful to your sense of worth.A sanctuary of healing? I was covered with bruises and scars, but the worst thing was to feel paralysed by fear. For too long, I accepted the degradation and humiliation, because somehow I was made to believe the violence was all my fault.A sanctuary of truth-telling? The verbal abuse and lies were so hurtful and demeaning. And the whole congregation was caught up in a conspiracy of denial. Towards the end I felt the hypocrisy of the situation very badly. It was all so false, and the threat of exposure seemed the worst thing of all. So every action and every word is not true and is not you and is not real. It is all lies and abasement. |

| They found no sanctuary in the Christian church, for the violence they suffered was perpetrated, legitimised and compounded in the heart of the church | A sanctuary of affirmation?

I went through absolute hell and felt like I was nothing, literally NO THING. I kept being told I was useless, hopeless, I couldn’t do anything right. I wanted to try harder and harder all the time to be good, to please them, to stop them hurting me - and the more I tried, the worse it got. There was no ‘I’ left in the end - just a shadow fading behind pillars and into walls.A sanctuary of justice? I was made to feel guilty because somehow I had failed to conform to the image of Christian wife and mother. Meanwhile, in spite of being accused of gross cruelty, he’s still a practising minister and was never held to account for his behaviour. But I’m the one who is made to feel bad - the wicked one who pulled back the veil of sanctimony and showed the filth beneath.A sanctuary of courage? It took me years to pluck up courage and speak to the priest, and it angers me that he had none - courage, I mean. I thought he might have spoken to the abuser, but that seemed to have been too much for him. So he did nothing. I could see it all over his face: "Please God, just make this woman and her unpleasant story go away". |

Centro de Estudios y Publicaciones, Lima, Peru. Reproduction of illustration from the book: La larga marcha de las Casas, CEP, Lima, 1974, by J.B. Lassègue |

She did go away - away from the church, from the community of faith she had loved and served for a lifetime. She was abandoned and desolate, shamed into silence. I was speaking recently with a woman who struggles every day to find a reason to live in the aftermath of hideous sexual abuse at the hands of a pastor to whom she turned for comfort and counselling, and who claimed this was part of God’s plan for her healing. Since then, she has tried and failed to find compassion, justice or restitution from church leadership and institutions. No sanctuary for Joanna? But the perpetrators of violence against her find refuge in what she describes as an impregnable fortress, built to protect the powerful and respectable, and to keep out folk like her and the people she encounters in her daily work in a run-down part of Edinburgh: the poor, the homeless, the asylum-seekers, the chronically ill, the people who don’t fit into the tidy boxes of ‘decent society’. They’re too disturbing and polluting. I told Joanna about the Decade to Overcome Violence, and she responded: "Well, Christians know all about peace, because they sacrifice people like me to keep the peace. They cover up and deny and ignore violence in their midst. The leaders humiliate the victims, and then silence us: out of sight and out of mind. All the church did was hurt me and then abandon me, and now I feel like I was only made by God to get punished for the bad things powerful people did to me." She spoke with anger. Her anger is better than the terrible soul-destroying despair which has laid waste the possibilities of flourishing and fullness in her life. Her words are better than the desolation of being silenced. They at least give Joanna the power to name her experience as violence. Writing about the Programme to Overcome Violence, German Evangelical Church bishop Margot Kässman claims ‘Few church leaders see violence within the churches as a major question to theology, a threat to the very being of the church; and some male church leaders still legitimise it... There is no way in which the churches can speak credibly about violence in society at large as long as they are not willing to deal with it within church walls.’2 |

| There is no way in which the churches can speak credibly about violence in society at large as long as they are not willing to deal with it within church walls | Perhaps there is no way in which the churches can speak credibly about violence at all, because our theologies, traditions, histories and practices have been deeply implicated in creating the many layers and interlocking networks of human structures sustained by violent means. And perhaps church leaders fail to comprehend the fundamental challenge of vio-lence to theologies and communities of faith, because they (we!) are the beneficiaries of a system which refuses to name and acknowledge the violence for which it is (directly or indirectly) culpable. Those who have the privilege and power to speak on behalf of Christianity, across confessional, theological and geographical borders, have too often claimed that the worst excesses of violence, destruction and atrocity - even those committed in the name of their particular religious brand - are regrettable aberrations, isolated from the benign and pacific intentions of the religious establishment and its guardians. Or they have excused, justified, blessed or sanctified the systems and structures which have diminished, harmed or destroyed unnumbered, unknown and unnamed peoples and communities. I am haunted, in this time of renewed crisis in the Middle East, by the global epidemic of cruelty against women and girl children, the running sore of sectarianism here in Scotland as well as Northern Ireland, economic devastation in Africa, the destruction of Indigenous Peoples and their lands... an endless litany of pervasive, adaptable, tenacious, brutal, subtle violence. I am haunted and overwhelmed and confronted by the question, posed here by Jewish theologian Marc Ellis: ‘The Christian world carries a burden into the present as a prime carrier and perpetrator of atrocity... The difficulty of Jews addressing a God who permitted atrocity on a mass scale against them is compounded in Christian communities that have sponsored atrocity for centuries. For what Christian language can be spoken after conquests that stretch centuries and continents beyond the Holocaust?..Is there a path beyond a religiosity that sponsors and is silent before violence?’3 What Christian language can be spoken? Is it the language of our scriptures - from Genesis to the Apocalypse a story of faith couched in the imagery of murder and revenge, blood-lust and war, rape and torture? Individuals are exploited and enslaved. Nations are invaded and colonised. Tribes are subjugated. Women are consumed and commodified. Sexual violence is accepted and eroticised. Children are disregarded and slaughtered for the sins of others. Jesus of Nazareth is humiliated and executed by an occupying power, acting in league with the religious establishment. And these biblical realities remain embedded in the social, economic and cultural realities of a globalised world. The alternative stories of subversion, resistance, human equality and radical community have been muted, dismissed orspiritualised out of harm’s way. Is it the language of those religious officials and power-brokers who have traditionally enjoyed privileged access to, and control of the sanctuary? They have delineated the boundaries between insiders and outsiders; between clean and unclean; between respectable and shameful, holy and contaminating, normal and different. Their words and their architecture express the potency of might and height, away from the earthbound, the everyday and the ordinary. Their theology has been used to legitimise male dominance, confirmed by a masculine God whose judgement, action and desire for the world has been understood to provide divine confirmation of mastery, subordination and obedience as appropriate patterns of human behaviour. In Durham Cathedral a thin black line is set into the marble floor near the back of the building, far from the altar. It marked the boundary beyond which women were prohibited to venture. That control has not just been a matter of gender, and it has been imposed in the name of Jesus Christ both to exclude and to incorporate subjugated peoples in mission stations and slave plantations; in religious institutions where children were ‘assimilated’ by forcible removal from their families to be brought up as white Christians. Dispossessed or disabled, gay and lesbian, deaf and blind: so many for whom the words, symbols and dynamics of worship have been disorienting and disempowering, failing to name, address or celebrate the realities of their lives. And historically the hierarchies, rituals and structures of the church have been used to interpret and legitimise social structures of mastery - patriarchy, colonisation, capitalism - by linking them to the sacred and claiming them to ordained by God. What Christian language can be spoken? Is it the language of those men in positions of authority and leadership reported in Living Letters who have normalised the violation and abuse of women in the church and thereby hidden it under a veneer of sanctimony; men who ‘frequently explained violence on the basis of culture’ or ‘queried the definition of "vio-lence", wanting to distinguish between violence that resulted in death, and ‘just hitting’.4 If we continue to use and listen to this language, spoken in and on behalf of the Christian church, we collude with definitions of violence which serve the powerful and silence the vulnerable. Men who abuse their power over women often find that physical force and threat is a useful strategy - but it is a means to an end which can be achieved in a variety of ways. The end is to control and delineate the life of another, and if that is considered an acceptable objective, a variety of physical, psychological, sexual, cultural and institutional forms of surveillance and coercion will be legitimised and normalised. They will not be defined as violence, except if used to excess - and who defines what that would look like? Those who want to distinguish between death and ‘just hitting’? |

| Will our churches be fortresses of refuge for the powerful perpetrators of violence, or communities of courage, where hospitality is offered, and diversity celebrated, and abuse confronted with honesty, care and integrity? | So gender and sexual violence have flourished as acceptable, normal, erotic patterns of behaviour because men (including men in the church) have asserted the right to possess and use women’s bodies and labour. One wife-beater claims ‘domestic violence is rooted in two things: the authority you believe you should have over your wife, and the services you expect to get from her.’ But haven’t countless men benefited from the same expectations - and haven’t the institutions and officials of the church throughout two millenia? Physical force and cruelty as a means to exert power over those considered of less intrinsic value or importance, is simply one end of a continuum of personal, cultural, economic and religious norms which are deeply embedded in most societies. Religious hie-rarchies and theologies have played a central an continuing role in the social construction of processes to legitimise, excuse, condone and sanctify the exercise of domination. These processes are fluid, but can only be understood in relation to structures of power and control. The Spanish invaders of Latin America justified conquest in the name of their God of salvation, and condemned the violence of the indigeneous Aztec religion. But they did not perceive their own actions as violent.5 Western Christians confess, in retrospect, their horrible complicity in the Holocaust, but are not so willing to acknowledge how the Bible has been used against their Palestinian sisters and brothers to ‘silence us, to make us invisible, to turn us into the negated antithesis of God’s "chosen people".6 Around the world, church leaders and pastors still minimize and trivialise the suffering of women, while counselling them to self-sacrifice, duty, patience and submission for the sake of the gospel. How can danger and harm to the wellbeing of any person made in the image of God be good news? What Christian language, then, can we speak ? Is there a path beyond a religiosity that sponsors and is silent before violence? That is the stark challenge if we in the churches, who have ready words of pious peace where there is no peace, can dare to embark on a Decade to Overcome Violence. "I suffered violence. For years I didn’t call it that. I knew it had harmed me - I knew HE had wounded me, betrayed my trust, exploited my weakness, imposed his will on my body and left his imprint on my soul. But I was expected to absorb it, to take the blame for it and to keep quiet about it. Why did these things happen to me, and why doesn’t the church accept responsibility?Here is a language which can bear the weight of theological integrity. It is the proclamation of those who, with great boldness, cost and a theological clarity fired in the searing flame of their experiences, are choosing the path of prophecy: seeking to reveal the true faces of violence in the church, and to call us to account by rupturing the smooth veneer. The Vision and Mandate for the Decade to Overcome Violence calls for Christians to listen to the stories of those who are the victims of direct and institutionalised violence in the church. Because they are usually shut up - kept quiet by exclusion, fear, poverty, marginalisation, debilitating inequality and its social mores - it has been rare to hear from these people and communities, and rarer still to be touched and changed by them, as Jesus was by the outcast bleeding woman. Can we create safe spaces to listen and share, not with patronising concern which leaves the structures of domination and control intact, but attentive to the possibility and hope of transforming justice? Will our churches be fortresses of refuge for the powerful perpetrators of violence, or communities of courage, where hospitality is offered, and diversity celebrated, and abuse confronted with honesty, care and integrity? I long for the church to be a supportive community. A place of friendship, fun and enjoyment, celebrating life and God. A sanctuary of courage, willing to challenge the causes of violence; not a place to hide from or conceal real suffering. I want to be all I can be. If only the church could be a place where it’s safe to be just who we are - real flesh-and-blood-and-heart human beings, made by God, loved by God and redeemed in Christ.7A place of God’s abiding, to be a sanctuary and a light. Lesley Orr Macdonald is Associate Secretary with ACTS (Action of Churches Together in Scotland), consultant for the WCC DOV - Overcoming Violence Against Women and a member of the Advisory Group to the Justice, Peace and Creation team of the WCC.

Notes

1. Living Letters: A report of visits to the Churches During the Ecumenical Decade (WCC publications 1998, see especially pp26ff) |